THE LAST PROJECT OF LEANDRO LOCSIN

The Church of the Transfiguration in the Benedictine

Monastery of the Transfiguration in San Jose, Malaybalay, Bukidnon, achieves a

certain mythical status as the last project of a great man. I went to Mindanao to see it

My initial impressions of it had come from the evocative

Neal Oshima photographs in the book “The Poet of Space: Leandro V. Locsin”,

written by Arch. Augusto Villalon and published in 1996. A March 2010 conference at the Paul VI

Institute of Liturgy on the vast grounds of the monastery presented the chance

to see the last church, and presumably the last structure, that the late

Leandro Locsin, National Artist for Architecture, had designed.

There are actually two monastery complexes on the

property. The “old” monastery is only 27

years old while the “new” monastery, designed by Arch. Locsin, is 15 years

old.

The conference on church architecture took place at the

“old” monastery but we had four opportunities to travel to the “new” monastery to

see the Locsin structure. It was

providential that we would first arrive at the “old” monastery because it

turned out to be a reference point for the Locsin structure. I was struck by the resemblance of the

structures there to the new church that I had seen in Arch. Villalon’s book.

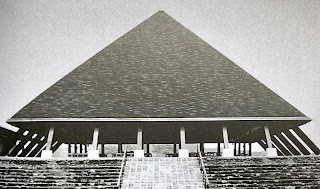

The old monastery was designed by the late Cecilio Maceren,

a Cagayan de Oro architect whose work deserves more recognition. He arranged three steep pyramids of varying

sizes around a courtyard. The largest

pyramid is the chapel (where the conference took place), followed by the

dormitory and the library. The

processional approach up the driveway rewards one with an exceptional orchestration

of views, the kind of architectural cinematography we do not often see these

days.

The three pyramids represent the three tents mentioned in

Gospel narratives of the miracle of Jesus Christ’s transfiguration, when the

apostles Peter, James and John witnessed Moses and Elijah appearing with Jesus. Peter had said “Let us build three tents

here.”

Catholics commemorate the Feast of the Transfiguration on

August 6 every year. On that day in

1981, in the company of his Benedictine companions and after a long search for

an ideal monastery site, Malaybalay Bishop Prelate Francisco Claver, SJ,

declared “Let us make three tents here”.

Maceren’s monastery complex was inaugurated on August 6,

1983. It did not take long before word

spread of the chanted liturgies taking place in its acoustically perfect

chapel. Small groups grew into

overflowing crowds of visitors who traveled great distances to hear the

Benedictines pray. The need for more

space became apparent. The chapel would

need to become a church.

Almost ten years later, and with the help of industrialist

Manuel Agustines, the Benedictine monks availed of the services of Arch. Locsin

to design a new church and monastery. In

the transfer from the old to the new monastery, Arch. Locsin brought with him

the idea of the pyramid. The three tents

of Maceren became the one tent of Locsin. The iconic image of Locsin’s church

is rooted in precedent, in the most profound and resolute way.

It is interesting to come to Malaybalay and see the context

of a last work, not just the immediate physical landscape of Maceren’s three

tents, but also the landscape of Locsin’s accomplishment. Clearly the steep roof floating majestically over

the ground plane was an archetype central to Arch. Locsin’s imagination. But he had never, as far as this author can

recall, demonstrated the actual archetype in its essential form, until

Malaybalay. Numerous projects

demonstrated the notion of the floating object, but the object was rarely a

pyramid. The National Arts Center on Mt.

Makiling, Los Banos, Laguna, demonstrates the diagram, but in truncated form

since the roof stops short of reaching its peak.

Locsin’s original plan diagram is very simple: a square 18 meters wide, centered under a

pyramidal roof 25 meters wide. Six giant

steel girders at each side of the square plan project at a 45 degree angle to meet

their counterparts. The difference

between 25 and 18 is 7, divided into two ambulatories, or verandas, of 3 ½

meters width each. This ambulatory

provides a transition between inside and outside, a gracious gesture that Arch.

Locsin often used, while also creating a shadow-rich recess that permits the

roof volume to float. The architectural

drawings showed sliding glass doors defining the interior space, surrounded on

all four sides by an ambulatory, but these doors had not yet been installed

when the photographs in Arch. Villalon’s book were taken.

The new church is about a kilometer’s walk from the Maceren

monastery. The road curves through trees

and clearings in the trees, so the processional approach achieves a dynamic

quality. The parallax of Maceren’s three

tents becomes the parallax of Locsin’s church in the midst of the Malaybalay

landscape, including the mountain ranges in the distance. It also occurs to one in the course of that

walk that Maceren’s three tents become Locsin’s one tent in rudimentary explication

of the Trinity.

That reverie is interrupted when one gets close to the

building by the realization that the roof is not floating. Instead of a recess between roof and ground

plane, there is tinted glass in both fixed and sliding analok glass frames

hugging the line of the perimeter, visually bringing the roof down to earth. The ambulatory is gone. The visitor is thus thrust immediately

inside.

The ceiling, at 18 meters, is clad entirely in horizontal

wood planks, separated by the black steel girders that carry the load of the

roof. The wood ceiling casts a warm

glow. Near the center of the space, a

large boulder, found not far from the site, is used as the altar table. The lectern is a gnarled tree trunk adapted

to exalted use. Liturgical norms

stipulate that the altar table and the lectern be of the same material, but in

this case, the defiance works to liturgical advantage. The archetypal roof provides archetypal

shelter to an elemental rock and an elemental tree. It is back to basics, in a way that takes us

back to our beginnings in the deep recesses of time.

Dom Columbano Adag, OSB, who had been in charge of

construction prior to his retirement, explained that the interior space needed

to absorb the ambulatory. Benedictine

monasteries were often the seeds of urban development in Europe. Where a monastery was established, a

community eventually flourishes. At

Malaybalay, the community is in the form of hundreds of visitors who fill the

church on Sundays and holidays, and spill outside. The overflowing crowds at the Maceren chapel have

become overflowing crowds at the Locsin church.

Tall Indian trees in one straight line act as a barrier

between the church and the monastery.

Dom Columbano was kind enough to give me a tour of the new monastery,

normally closed to outsiders. A series

of arcaded courtyards, the monastery is still a work in progress, as about a

quarter of Arch. Locsin’s original monastery plan waits for funding. But what has been built so far demonstrates a

subtle Japanese influence, a quality of quietude that Dom Columbano and his

brethren continue to find conducive to their way of life.

Whereas the church building has no walls, except at the

sanctuary, the monastery in turn is defined by them. White masonry blocks of a lime-and-cement mixture

were manufactured on site to become the basic building block. The dynamic quality of Maceren’s monastery is

supplanted by the serene rectilinearity of Locsin’s. Whereas Maceren’s three tents are in some

sort of confraternity, Locsin’s design places the church in clear supremacy

over the monastery, which recedes into the background. Only the bell tower competes for visual

attention, seeming to mediate between the monastery and the church.

I suspect that it takes at least four visits to begin to

understand any space of quality. I

realized this in Malaybalay. If I were

to have written this article after the first two visits, I would not have been

able to relate the space to notions of the sacred, for the simple reason that I

could not bridge the gulf between Oshima’s photographs and the reality of the

vanished ambulatory. I am therefore

grateful that circumstances permitted me to witness the morning and evening

prayers of the monks. In both cases, the

liturgy of communal prayer helped me to understand the space.

On the last full day of our visit to Malaybalay, a few of us

had gathered in the pre-dawn darkness to join the monks in their 5:00 a.m.

Laudes, the prayers chanted before sunrise.

The pyramidal shape of the roof seemed acoustically perfect for the

Benedictine chants. Laudes was followed

by mass, and at the moment when the priest was raising his arms to consecrate

the host, the waking sun was beginning to shoot its first rays over the lid of

the distant mountains, washing the altar rock with its concurring light.

Our last visit the church was for the 5:00 p.m. vespers.

In the last chapter of Evelyn Waugh’s “Brideshead

Revisited”, the protagonist describes the flickering of the tabernacle light in

the chapel of an ancient English Catholic family that he was revisiting after

many years. “Something quite remote from

anything the builders intended has come out of their work…a small red

flame...It could not have been lit but for the builders and the tragedians, and

there I found it this morning, burning anew…”

As incense smoke rose in an S curve by the side of the altar

rock heading towards the dark apex of the ceiling, this last chapter came to

mind, as a kind of summation of my visit here.

This was the same smoke that rose by the side of many other altars, many

hundreds of years ago, in many other places.

There was a power outage here in the gathering dusk of Mindanao, and as

vespers were ending, the sun brought its diminishing light only to that smoke.

Arch. Locsin’s Church of the Transfiguration was completely

one with nature and with the liturgy.

(Published in BluPrint June 2010)

(photo from "Leandro Valencia Locsin: Filipino Architect" by Jean-Claude Girard, Birkhauser, 2022)